Of course, the generation gap that I am referring to is the technological generation gap that exists in the photographic world today. On one side of the chasm you have new, digital technologies that reduce the visual world to an ordered series of 0’s and 1’s stored within a digital file. On the other side of the chasm are the traditional photographic technologies that rely on film and emulsion to be the storage media for the image.Â

If you are young enough to be a product of the digital era, it is likely that all of your accumulated photographs already reside on your computer, so you will find yourself standing securely on one side of the digital divide.  If you happen to be old enough, it is likely that all of your accumulated photographs are of the traditional film type, and it may be that you are quite content with the status quo. If so, then you will find yourself standing equally secure, but on the opposite side of the digital divide. In between these two extremes, however, are legions of photographers (myself included) who possess both digital images and film images, perhaps numbering into the thousands for each type. For these photographers, questions often arise as to the best method of moving an image back and forth between film and digital media.

Over the past years, I have struggled with some aspects of the film-to-digital, digital-to-film conversion dance. Although not an expert in these areas, I have learned a few things from both my successes and failures, so I will share them with you in a seriously serious series entitled “Bridging the Generation Gap”.  Part 1 shall begin where I began my own journey into this brave new world, with 35mm film/slide scanners.

In 1993, there were no consumer digital cameras. Kodak had just recently announced the DCS 200, based on a Nikon 8008 camera body, but that was a professional 1.5 mega-pixel camera that sold for over $10,000. Without a lens! While there might not have been consumer digital cameras, there where plenty of computers around, and plenty of people who wanted to digitize their film-based photographs in order to edit, print, share and archive them. I was one of those people, and so I began my search for a scanner capable of digitizing the thousands of 35mm slides that I had accumulated over the years.

The first scanner I owned was a Nikon Coolscan LS-10e. This was a 2700 dpi – 8 bit per color channel slide/film scanner that was considered to be of excellent quality in its’ day (1993), and which sold for approximately $2000. This scanner would produce a 24Mb uncompressed tiff file from a 35mm frame. I can honestly say that I pushed this scanner system to it’s limit.  I can also say that this system was a nightmare to install and use. I use the term “scanner system” deliberately, because at the time this scanner was marketed by Nikon, there were three critical components necessary to create a successful scanning environment; the scanner device itself, the computer interface, and the scanner software provided by the scanner manufacturer.

To explain the shortcomings of the Nikon scanner system, I really must take you back in time and refresh your memory as to the state of the graphics world in 1993. Apple Computer was the name of the game, and a Mac was the machine you needed to have. Adobe ruled the graphics/imaging software world, and Photoshop Version 2.3 reigned supreme. In the PC world, the Intel Pentium chip had just been introduced, and this 60 MHz “screamer” could be had for as “little” as $878. If you were at the cutting edge, you would have been thinking of upgrading your Microsoft MS-DOS Version 6.0 to Windows for Workgroups Version 3.11. Woe unto the poor, misguided soul who dared venture into the graphics field armed with merely an Intel/Microsoft based PC.

Why was it so difficult for us PC guys to use our computers for digital imaging? If you examined Photoshop v2.3, for instance, you would find that the software was originally written and optimized for the Mac platform, and then (poorly) ported over to the PC platform. Ditto with the scanning software provided by Nikon for the LS-10e. Originally designed for the Mac, it too was a botched port to the PC platform.  Added to this unfortunate mix was the fact that the Nikon LS-10e driver relied upon a specific Adaptec SCSI interface board to communicate with the computer, and that particular Adaptec board had numerous issues with the extended memory managers that were a necessary part of the PC’s configuration back then. Despite all of the problems, Nikon and other imaging vendors recognized the huge market the PC represented, so it was “off to market” with whatever products they had at hand.

I could write a a very long article about all of the problems I had with the Nikon LS-10e scanner system, but that is not the purpose of this post.  Suffice it to say that for every scanning session, I had to reconfigure autoexec.bat files, config.sys files, reorder the devices attached to the SCSI daisy-chain, reboot the system, say my prayers, and then scan. If my prayers were answered, the scan would be successfully completed without crashing the computer two or three times.  When finished scanning, the entire process had to be reversed to enable normal use of the computer. Add to this the problems encountered, and the time consumed when trying to perform digital editing of a 24 Mb image file on a machine that could only “see” 640k of the file at a time, and you had a scenario in which a person had to be pretty motivated (or have had plenty of free time) to do any serious scanning. Having said that, the results obtained after exerting all this effort in scanning a slide or negative were excellent. The Nikon scanner was great at rendering an accurate and pleasing image file for those images that I scanned using it. But because of the enormous time commitment involve in the process, I never even came close to my goal of digitizing all of my old film-based images.

Two years ago, I decided that the time had come to reopen the book on my slide/film scanning escapades, and so I again ventured out into the 35mm slide/film scanner marketplace. What I discovered was that the slide/film scanning situation had changed very dramatically since my last foray into the arena a decade ago.  After examining the offerings available, I settled on a Konica/Minolta Dimage Scan Dual IV 35mm Slide/Film Scanner (whew… that’s a mouthful).Â

This scanner is a 3200 dpi – 16 bit per color channel 35mm slide/film scanner that also accommodates APS film. This scanner will produce a 70Mb uncompressed tiff file from a 35mm frame, or nearly 3 times the information capacity of the Nikon Coolscan produced file.  The scanner connects to the computer via USB 2.0, so it is simple, quick and readily available to most users. The scanner is supplied with the scanner utility software as well as a copy of Adobe Photoshop Elements. I paid less than $250 for this scanner in 2004.

My experience with this scanner has been diametrically opposite of my experiences with the Nikon scanner of the 1990’s. After the initial installation, which involved nothing more than inserting an installation CD into the drive and then plugging the USB cable into the computer, the scanner worked flawlessly. I have used this scanner to scan hundreds of slides, and it has yet to crash in the midst of the process. The Nikon Coolscan, on the other hand, would sometimes take two or three rebooting cycles of the computer just to achieve one successful scan. The slide holder (which can be seen in the photo above) holds four slides at a time. Now that I have become familiar with the software and have established a usage routine, I can prescan four slides, apply minor image correction and cropping to each image, and complete the final scans on all four images in less than ten minutes. So at a rate of about 20-25 slides per hour of work, I am slowly making a dent in my digitizing efforts.

Quality of Scan Issues

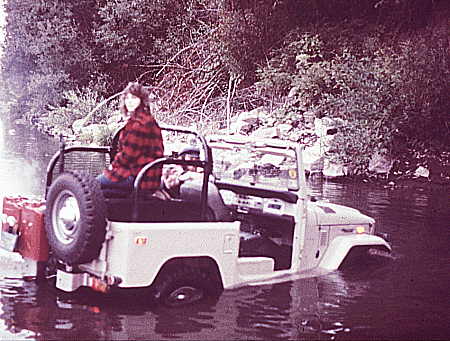

For the type of usage that I have put my scanners through, I can make a few general observations regarding image quality. The first observation is that the quality of the scanned image is directly related to the type of film that is scanned, regardless of which scanner you use. The results of both the Nikon and Konica/Minolta scans reflect the fact that grainy films produced poor scans from each. For example, here is a scan produced by the Konica/Minolta scanner from a GAF color ASA 400 slide film (which is considered a grainy film).Â

This scanned image has lost most of the sharpness that exists on the original slide. Additionally, if you examine the shadow areas at the top, the grain of the film becomes apparent, much more so than when the film itself is examined under a loupe.

And the following example is also GAF ASA 400 slide film, scanned with the Nikon Coolscan. This photo was taken in Yosemite National Park at night, using a time exposure (notice the stars in the sky). You can really see how the grain is exaggerated in the sky with this scan.

The second observation is that both scanners produced excellent results when the film in question was a good exposure taken on a fine grained film. Here are two more examples to illustrate this point. The first is a photograph taken with Fuji Velvia 50, considered to be a highly saturated and fine grained color slide film, and originally scanned with the Nikon Coolscan:

Notice the deep saturation of the resulting scan, and also notice that there are no grain artifacts in either the background, or in the “skin” of the Spanish Shawl nudibranch. The following photograph of a Corvette fender (everybody has a photo of a Corvette fender, don’t they?) was taken with Kodacolor ISO 100 film, and it was scanned with the Konica/Minolta scanner:

In examining the photo above, you will see bright saturated color, and no hint at any graininess. The detail in the images has been retained in the final scan, and artifacts are kept to a minimum.  Overall, I have been very pleased with the quality of the scans that I have made with both of these systems,  but I have been extremely pleased and surprised at the ease of installation and use of the newer generation Konica/Minolta scanner.

As a concluding thought, I would say that the goal of digitizing my collection of slides will probably be accomplished eventually, but not in the near future. At a rate of 20-25 slides per hour of work, the scanning process is still a slow procedure. Fortunately, I do not shoot with film anymore, so my collection of film-based photographs will not be growing. In the meanwhile, it is quite enjoyable to see pictures taken long ago become available for viewing and sharing on a computer platform.