Night photography in the Ozarks can be difficult. The narrow, winding, dark roads are hazardous to drive at night, and the abrupt falloff from lane edges to drainage ditches means there is usually no shoulder to park alongside the roadways. While there are areas in the Ozarks with dark skies, most of these areas are quite inaccessible (there are good reasons why the Ozarks remained a “semi-arrested frontier” for generations, the ruggedness of the terrain being one of them). Combine this with the warm and humid air of the region, which creates lots of long exposure noise in images, and one can see why night photographers in the region are always on the lookout for alternate locations to shoot.

That is why, when Darren White posted an invitation to his friends to join him on a photographic scouting trip in Kansas recently, I immediately jumped at the opportunity. Not only does Kansas have reasonably dark skies, it also features many wonderful foreground subjects with easy access and wide-open horizons. And shooting with Darren is always inspirational and educational. What could possibly go wrong? Besides the weather, which rained or created foggy skies most of the trip. Besides the electrical system going out in my RV. Besides the water pump in the RV dying. Besides the hundreds of pounds of mud I pressure washed from every nook and cranny underneath my truck. These were merely annoyances compared to what I gained by participating in this scouting trip.

While I do not have many night images from this trip due to the weather, we did manage to explore a trove of locations that will provide many, many night images in the future. Meanwhile, the photography I did manage to get in turned out OK, so I thought I would share some of the images and locations through this post.

Day 1 (Wednesday) and Day 2 (Thursday)

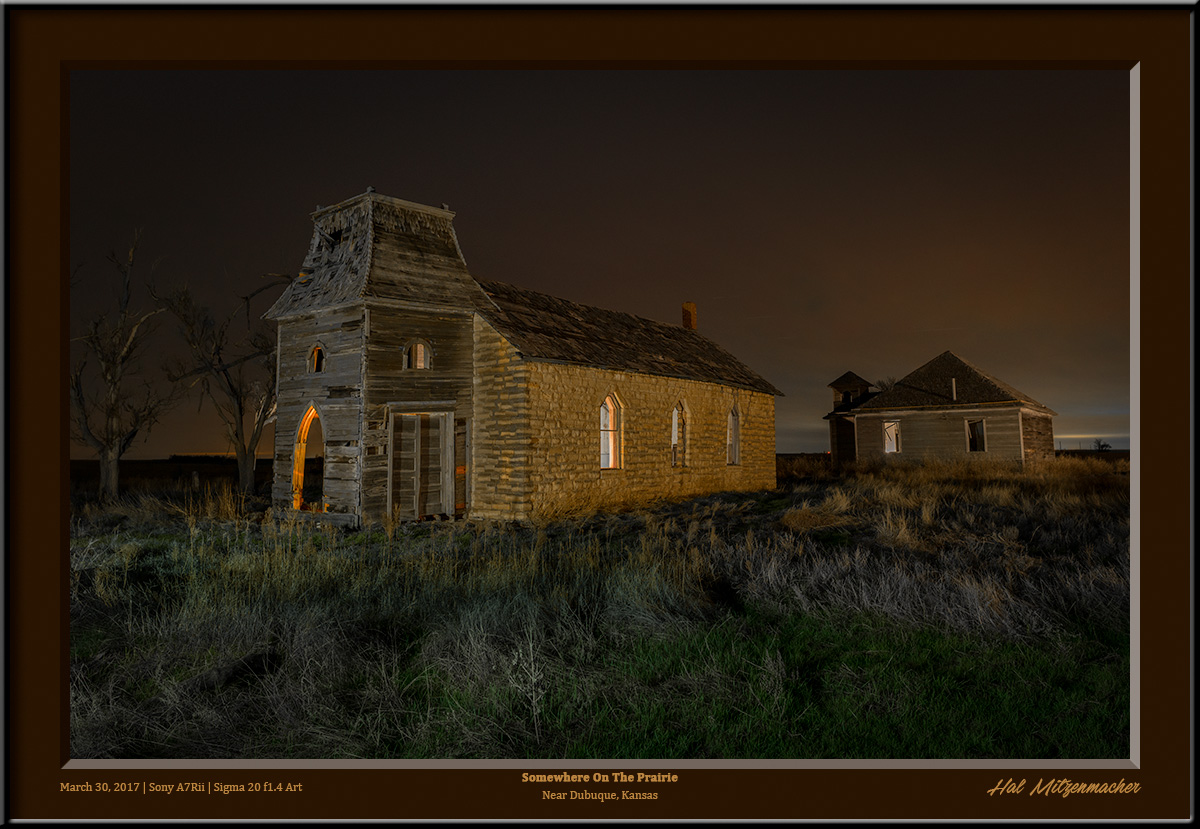

Day 1 was spent driving from the Ozarks to Cedar Bluff State Park, located at Cedar Bluff Reservoir in central Kansas. After a long rainy drive, I spent the night making repairs to the RV and resting up for the following day. On Day 2 I met fellow photographer Mike Spivey at a location near Dubuque, Kansas, where we awaited the sunset in order to photograph this old church and schoolhouse, The sunset did not disappoint, and we were rewarded with some rich, warm tones to work with. It was here that we met Derek Ace, a photographer from Wisconsin, who joined us in shooting these structures.

Derek had just arrived in Kansas after a long drive from Wisconsin, so he departed immediately after sunset to catch up on some needed rest, while Mike and I continued to shoot the old abandoned church until about 11:00 pm. It was pretty apparent that the Milky Way would not be making an appearance early the next morning due to the clouds, so I made my way back to camp at Cedar Bluff State Park.

The sky decided to play tease with me – when I arrived back in camp, the clouds had completely disappeared, so I set up the camera to take star circles around this giant fishing rod & reel for a couple of hours, while awaiting the Milky Way core, which would be rising in the wee hours of the morning. I settle down in the truck to take a nap, and when I awoke, the area was engulfed in fog. No Milky Way again.

Day 3 (Friday)

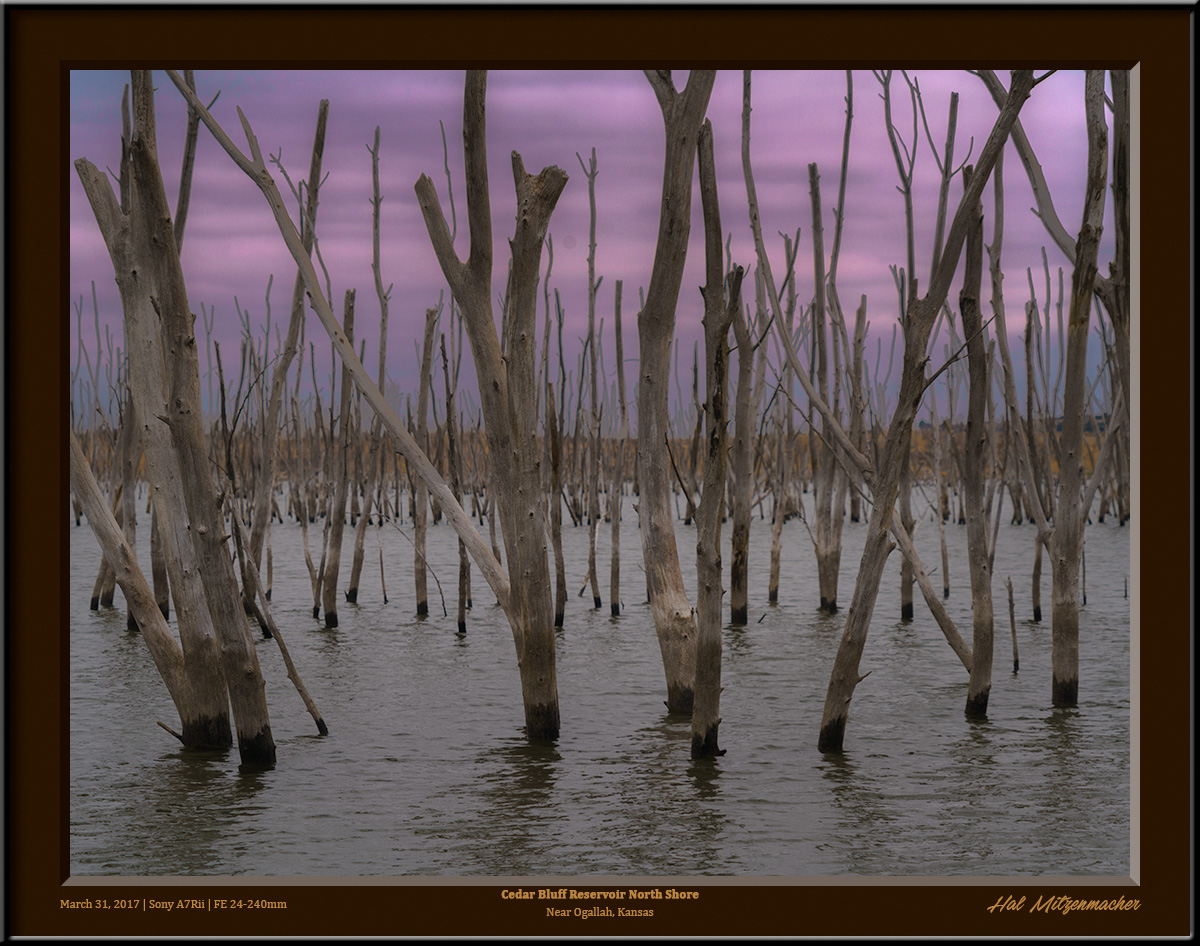

Several photographers met up on this, the first “official” day of the scouting trip, at 4:00 pm at Cedar Bluff State Park in central Kansas.. Included were Darren, Bob, Mike, Angie, Shari, and myself. Our first order of business, after getting acquainted, was to explore both the south and north shores of the Cedar Bluff Reservoir. The south shore is generally flat, but contains areas full of the trees that stick up out of the water. The north shore, on the other hand, has nice areas of rocky bluffs that are quite rugged and photogenic. I think that the Cedar Bluff area has great potential for night images when the sky and weather are cooperative.

Day 4 (Saturday)

Our intrepid group of explorers departed camp at 5:00 am, hoping to catch the sunrise at the Excelsior Lutheran Church, a beautiful structure near Wilson, Kansas, located in the middle of the Smokey Hills Wind Farm. The rains of the previous night and that morning made the roads too muddy for some of the vehicles in our caravan, so we toured around the area instead. Some locals informed us of a couple of attractions nearby, so off we went to check them out. Above is a view of Wilson Lake, near Wilson, Kansas. It has a reputation as a great bass fishing lake, and appears to be a location where the Milky Way might be captured, given the right conditions.

After visiting the towns of Lucas, Kansas (home of the wonderful Garden of Eden) and Wilson, Kansas, we headed over to Ellsworth, Kansas. Our group of photographers (now whittled down to four, as two opted to return home on account of the rain) explored around town, where it is apparently a thing to photograph grain elevators with leading lines from railroad tracks :)

Because of the extensive rains that had occurred, there were puddles everywhere, so what better time to practice my puddleography skills using my cell phone camera.

Continuing on from Ellsworth, we explored Fort Harker, Lyons, Ellinwood, Great Bend, and Ness City before heading back to base camp at Cedar Bluff State Park. There were several abandoned structures along the route, and I compiled a decent list of night photograph possibilities for future trips in my PlanIt! for Photographers Pro software.

Day 5 (Sunday)

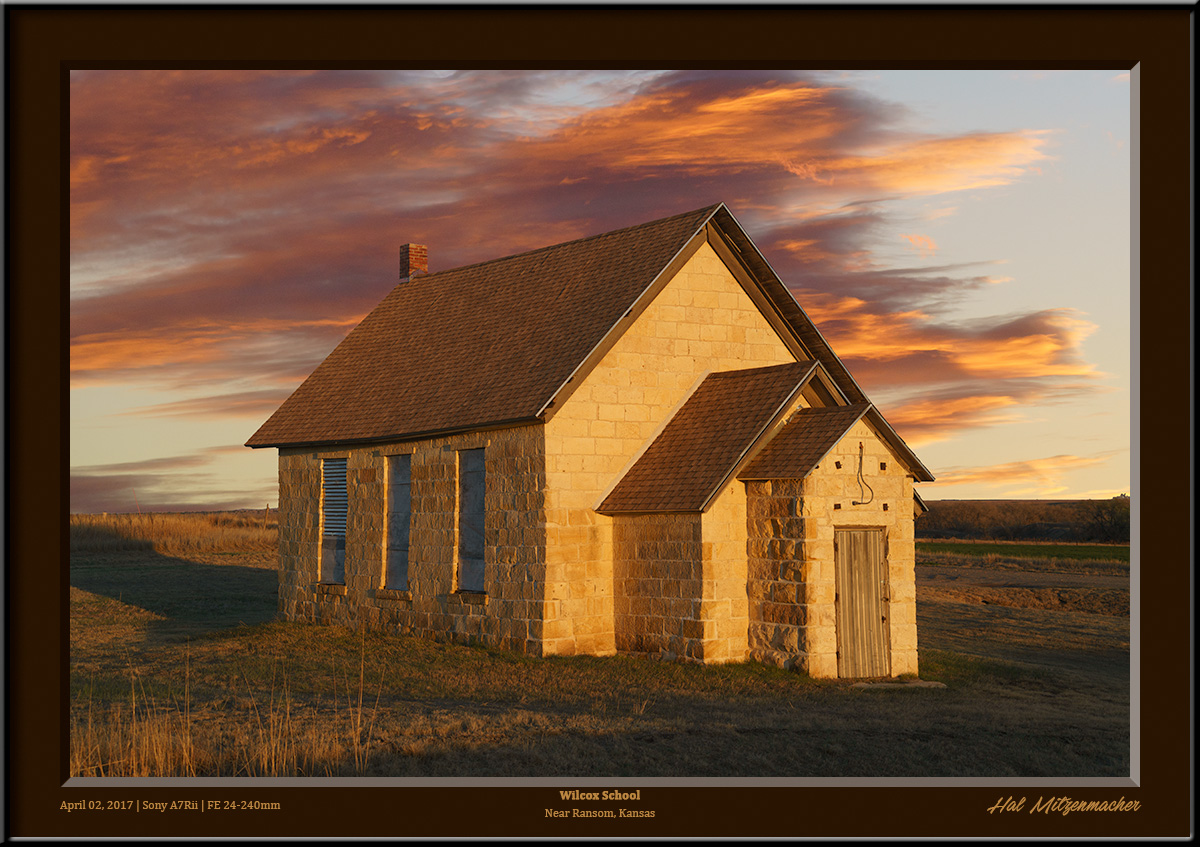

One more member of our group, Shari had headed home Saturday, so now there were just the three of us left, Darren, Bob, and myself. We decided to meet up for sunrise at 6:00 am Sunday morning to photograph the Wilcox School, about 15 minutes south of Wakeeney, Kansas. The sun was not very cooperative with our sunrise plans, so I attempted a few “faux fog” shots of the schoolhouse, which Darren had just taught me. What I learned is that I had wasted my money buying a Tiffen Double Fog 3 Filter. Just breathing on the front lens element provides a far better result, and you can look through the live view and snap the shutter when the fog effect is just to your liking. An interesting technique I will certainly employ from time to time in the future.

It was now time to head over to Monument Rock and Chalk Pyramids for some daytime shots of the area, but not before stopping to look at some interesting sights along the way. At the Scott County Fairgrounds, in Scott City, Bob and I were at a loss to explain the reason for this gate. It reminded me of the scene in Blazing Saddles, where the army of bad guys stop in the middle of the plains to pay a toll at an isolated toll gate!

As a reminder of how transitory some subjects can be, here is a shot taken on another of the trips to Kansas that Darren was so kind to organize in August of 2016. A group of four photographers (including myself) spent hours at this old abandoned grain shed located on Jayhawk Road as lightning storms raged all around us. The photo opportunities that night were beyond amazing, and while I know that was a stroke of luck not likely to be repeated, I was still looking forward to photographing from this location again. Alas, we discovered as we drove past this structure that the roof, with the beautiful overhanging eaves, had collapsed! Oh well, I’m just glad I had the chance to photograph this building when I did.

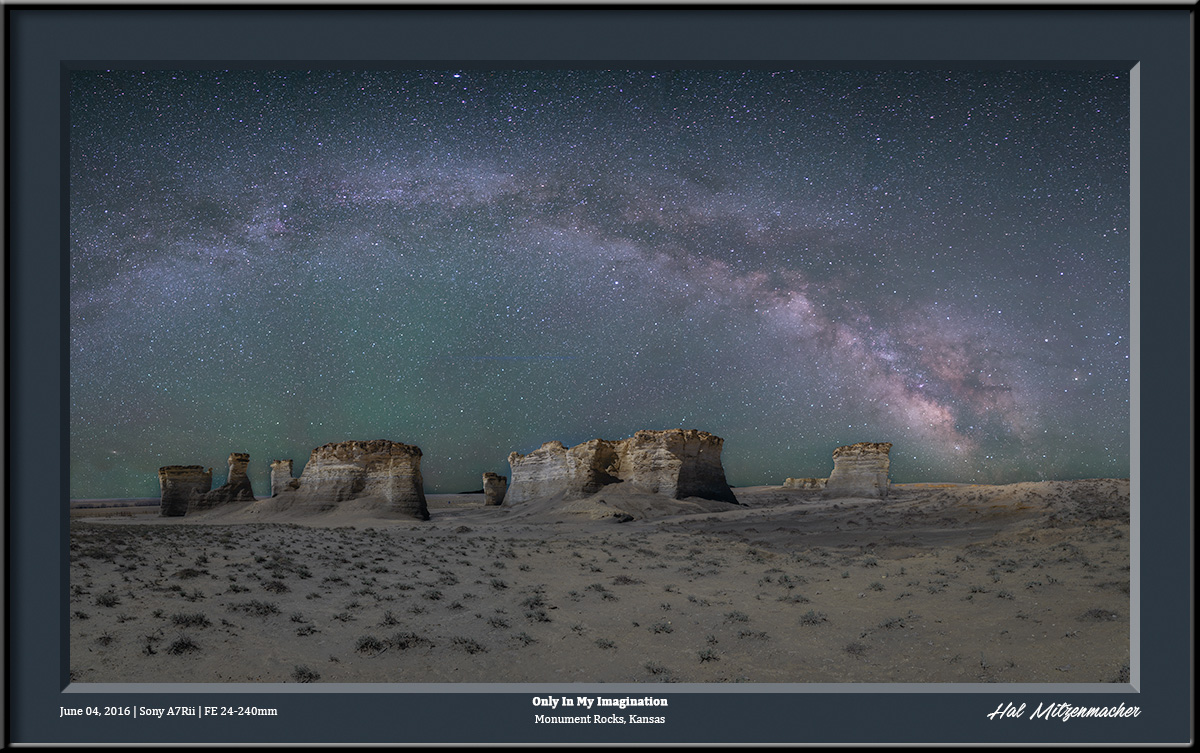

At this point, I would like to have said that I took these images on this scouting trip to Monument Rock and Chalk Pyramids, but when Darren contacted them they informed him the area was unavailable for special permission to photograph at night, due to calving season. This wonderful geographic feature is located on private property, and the owners have been quite generous in allowing the public to enjoy the area. The rules that are posted are simple to comply with, and if you contact them beforehand, they will try to accommodate your visit request if at all possible. I urge you to do your part to help keep Monument Rocks available for all of us to enjoy in the future.

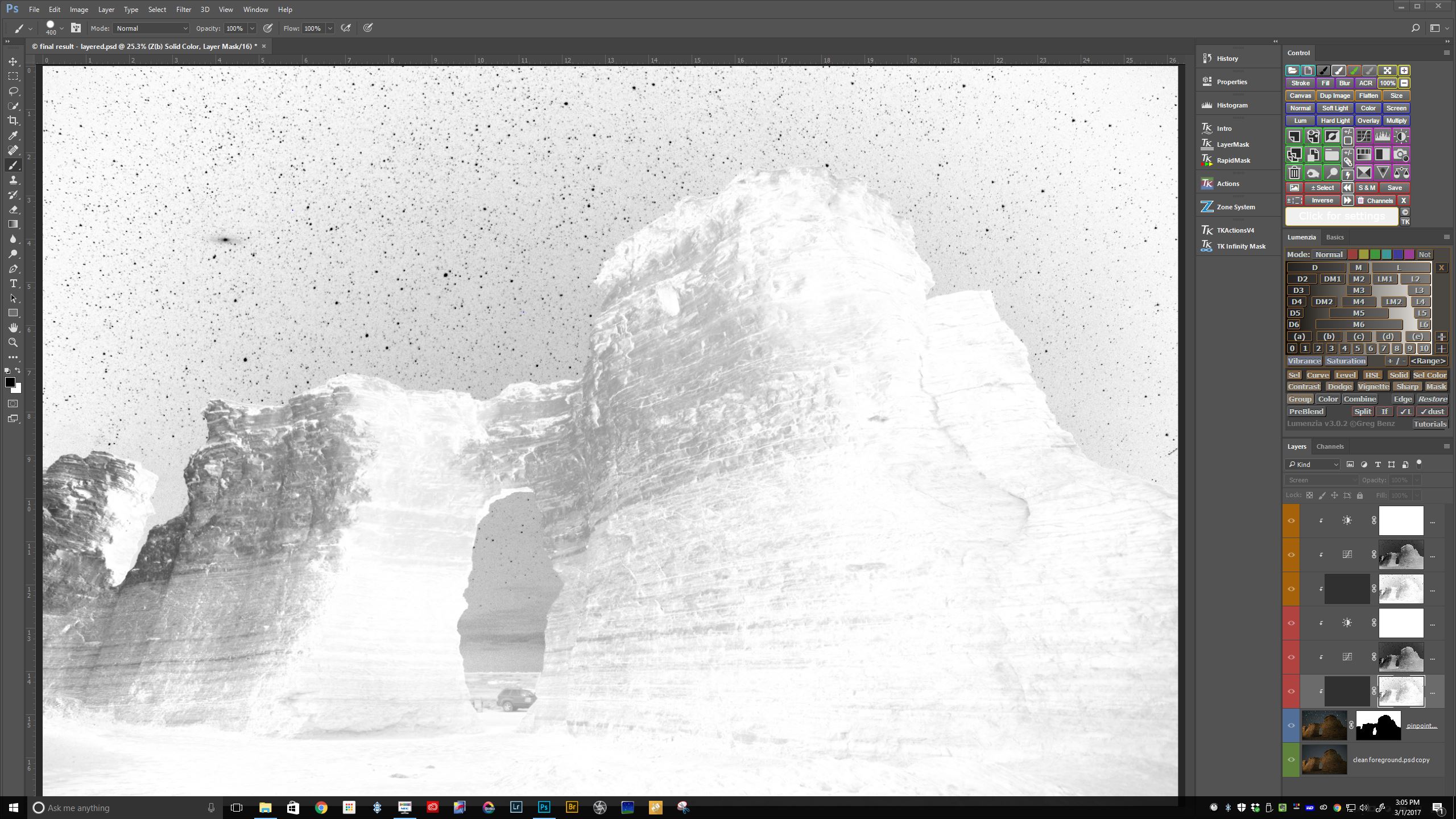

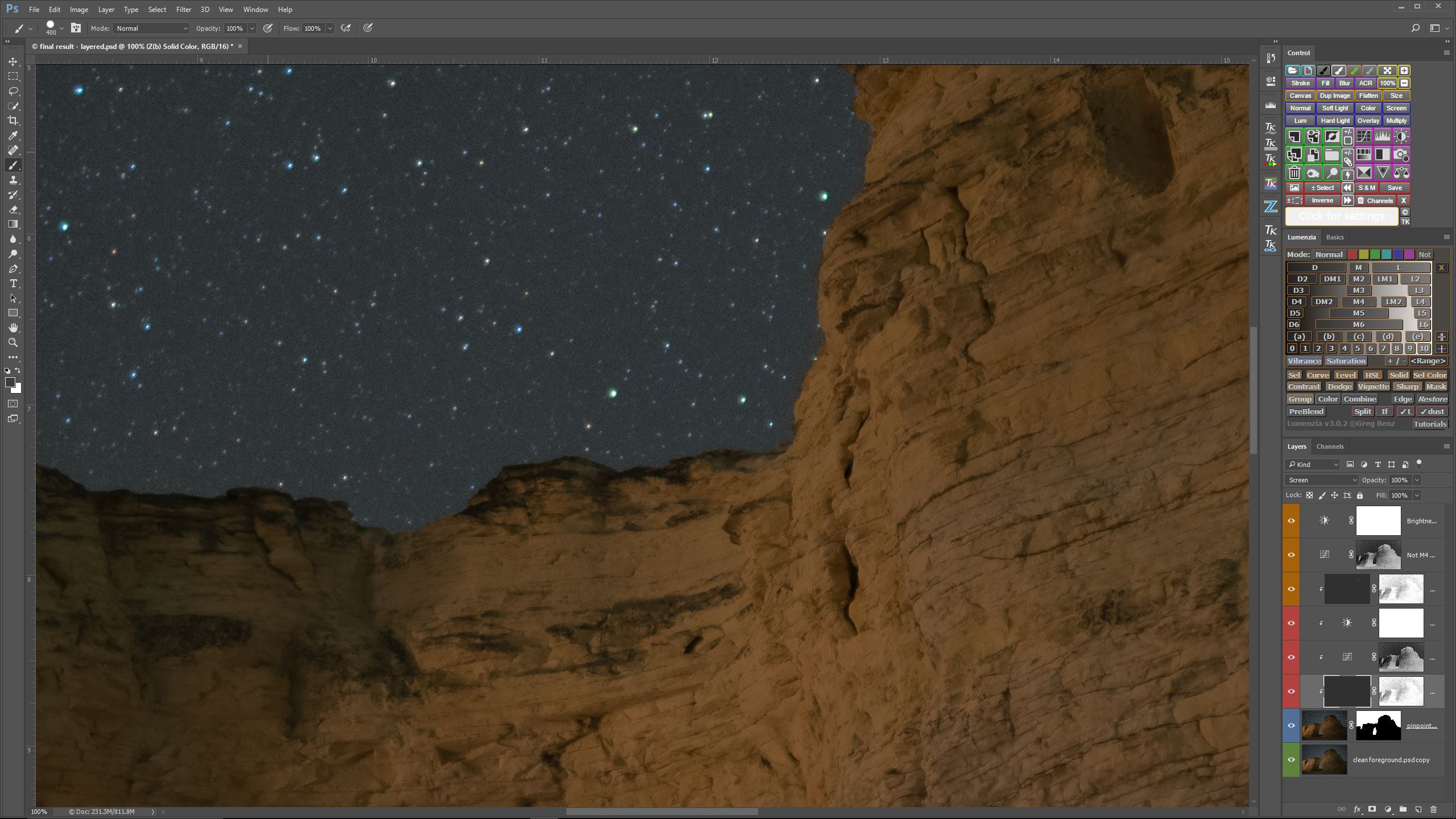

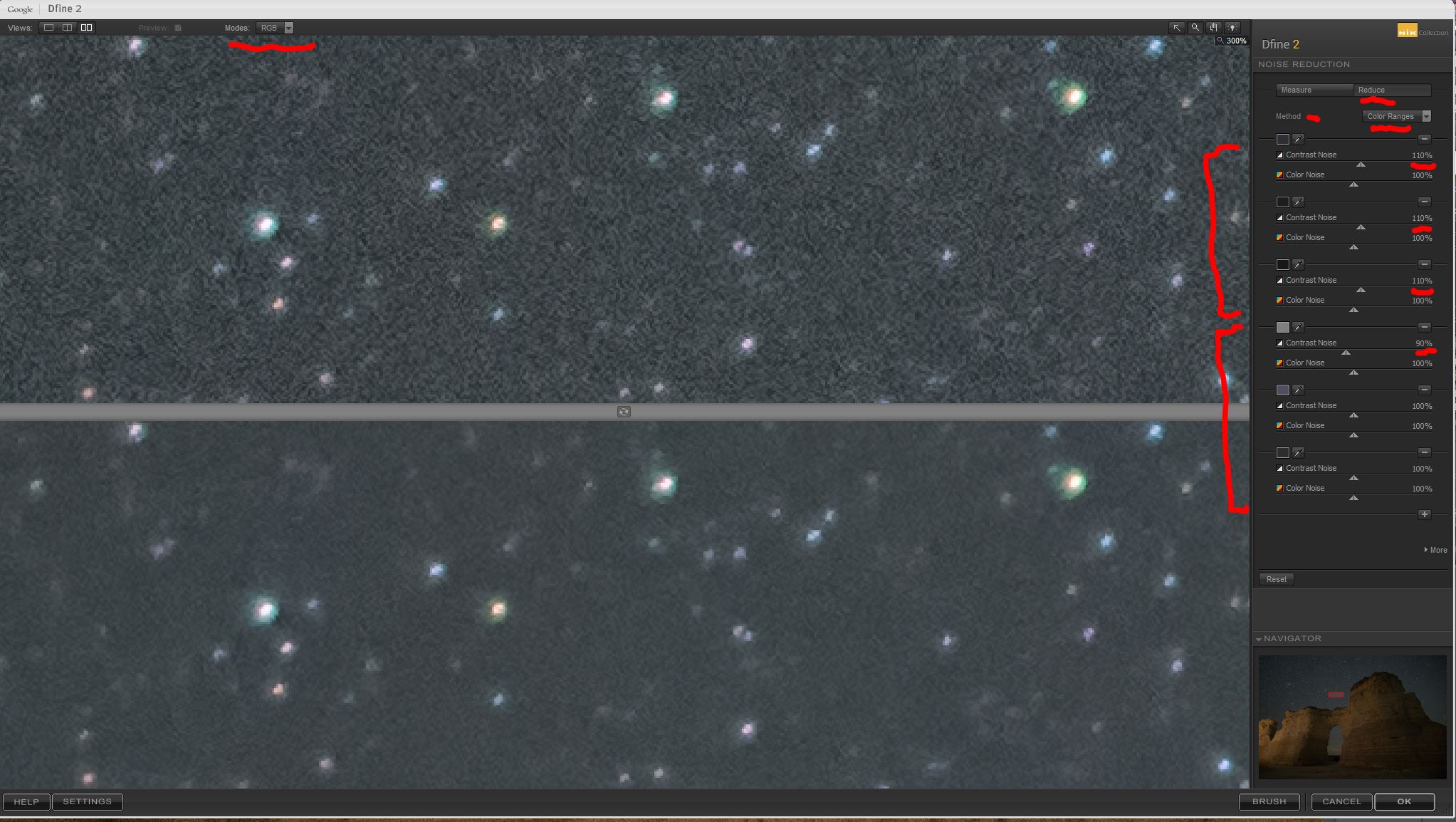

I was extremely hopeful to get a Milky Way panorama over Monument Rocks this trip, but due to circumstances beyond my control, I could not. So I faked one using a composite of a foreground panorama taken on this trip to Kansas, and a Milky Way sky taken last year in Wyoming. I’m allowed to imagine, aren’t I?

After photographing Monument Rocks we headed off to explore some of the small towns along Old Highway 40. In the town of Park, Kansas (population 129) we discovered a Catholic Church that I’m sure could easily hold 10 times the population of Park. This seems to be a common feature in small Kansas towns – huge churches relative to the size of the town.

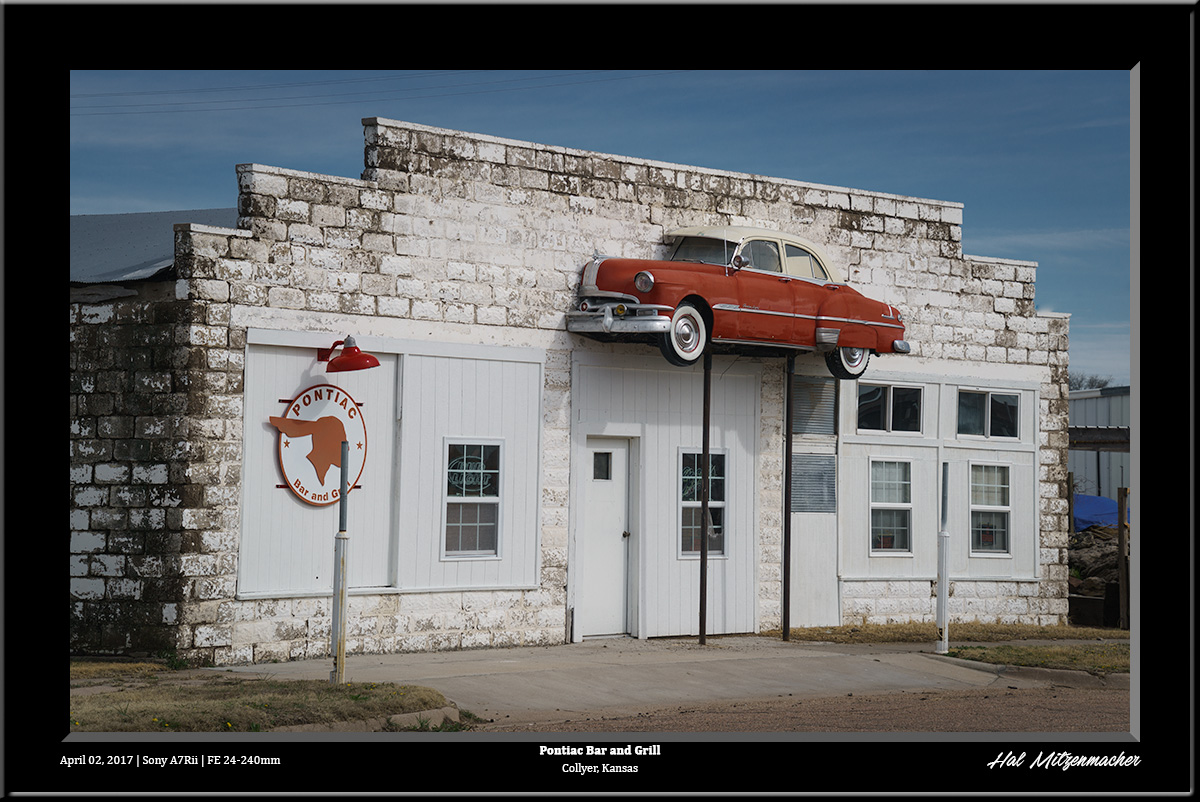

From Park, Kansas we continued on to the town of Collyer, where the main attraction seems to be the Pontiac Bar and Grill, even though it is currently out of business. It must be sorely missed, because, as Darren has pointed out, four locals inquired (hopefully) as to whether we were there to buy the bar! In case you were wondering, the other half of the Pontiac (it looks to be vintage 1953) is mounted on the rear of the building.

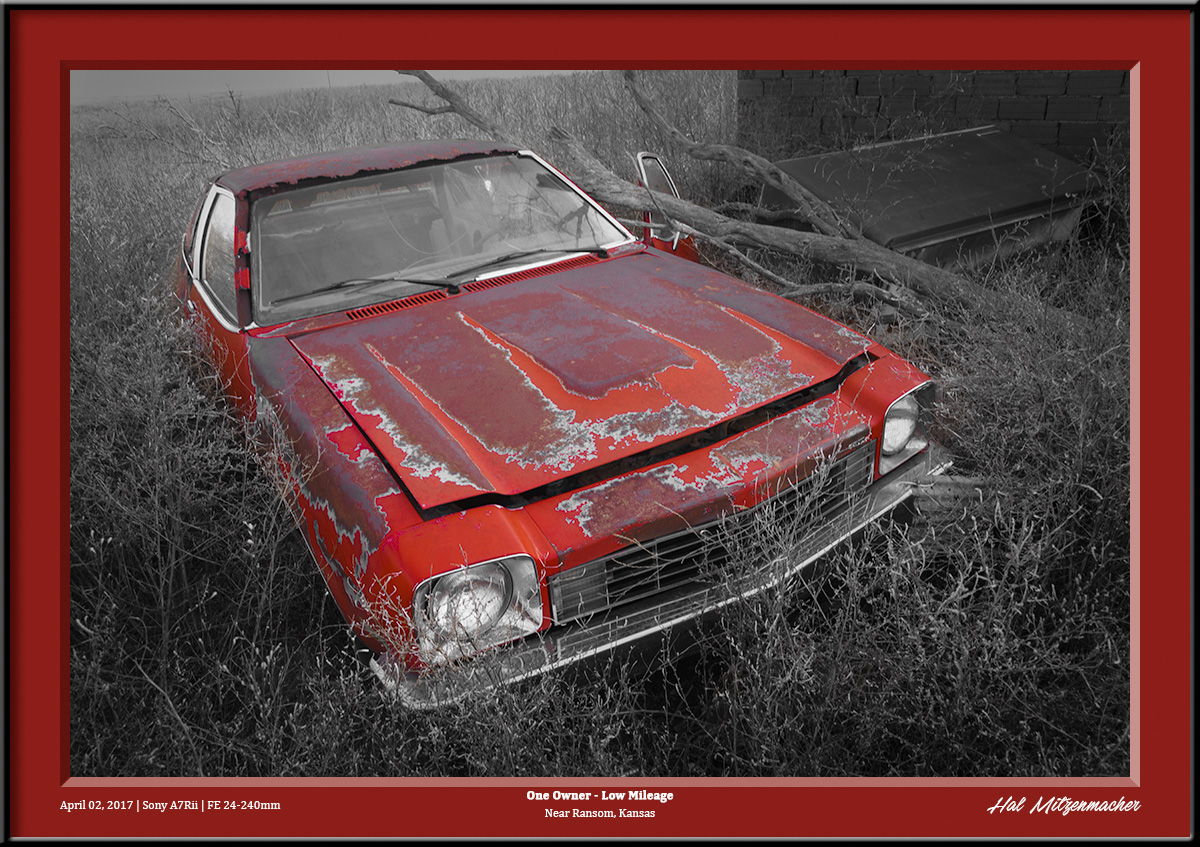

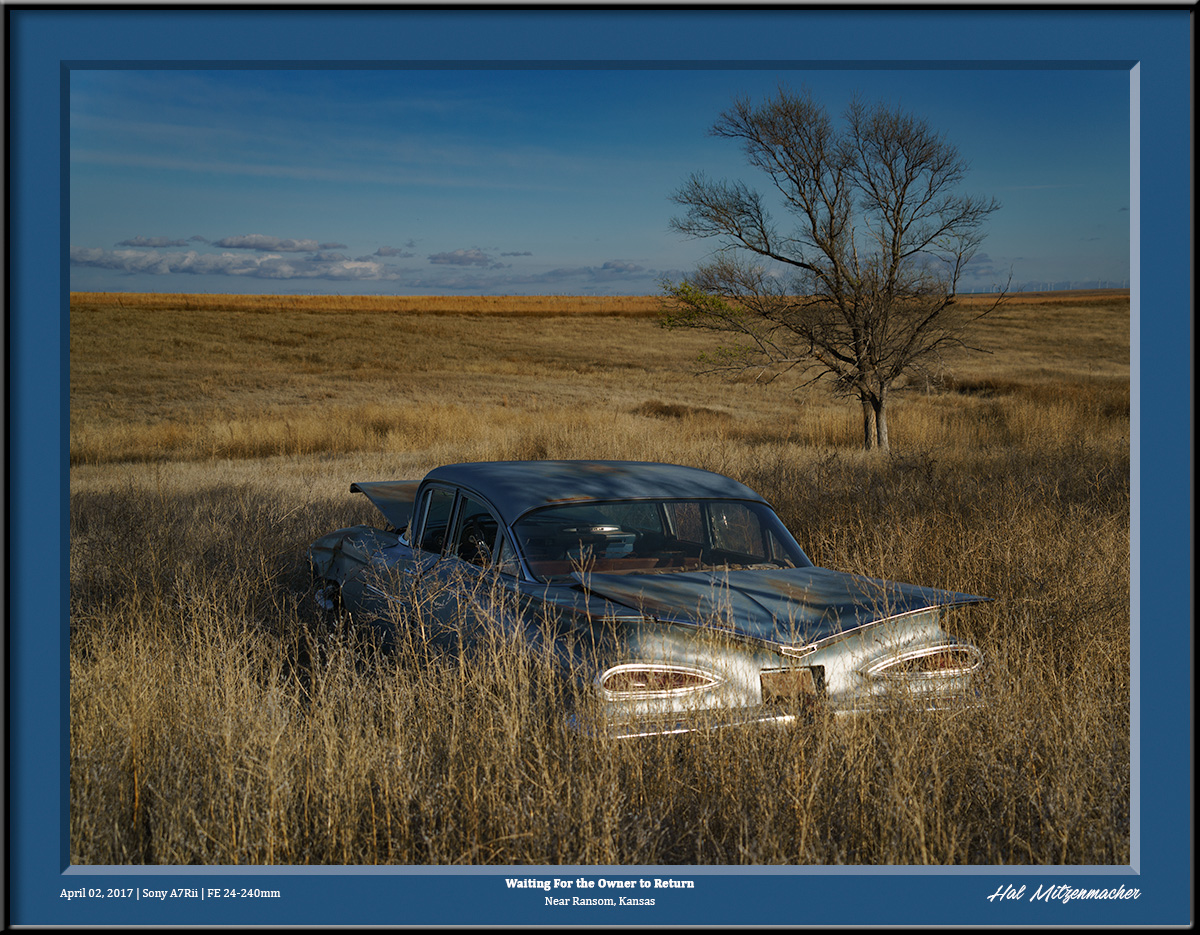

After finishing up in Collyer, we headed back to Ransom, Kansas to shoot sunset pictures of the old schoolhouse that we had visited earlier in the morning. Near the school was an old abandoned homestead, which included some interesting finds, such as the old vehicles scattered around the property.

We enjoyed some nice glow from the sunset, and it provided us with some really nice light to work with the schoolhouse. After sunset we headed back to Cedar Bluff State Park, where we intended to nap and await the rise of the Milky Way core early in the morning hours.

Rather than napping, I decided to try out a new (to me) light painting device called a Pixelstick. All was well, until this giant armadillo chased my into my camper for the night. When the alarm went off at 2:00 am to signal that it was time to go shoot the Milky Way, I popped my head out the door and discovered that fog had completely enveloped the area. Darren and Bob decided to start heading for home, and I decided to get a good night of sleep. The next morning I checked the weather forecast, and it wasn’t looking good, so I decided to head on back to my neck of the woods in the Ozarks.

Conclusion

All in all, it was a successful trip. I did not get any of the Milky Way photographs that I had hoped for; in fact, IÂ did very little night photography on account of the weather conditions. But the purpose of this trip was to scout out areas of Kansas that might be conducive to night photography at some future date, and on this count, the trip was very successful. I have shared some of the sites we visited, but have saved some of the best for later, when I can go back and photograph them the way I envision the scenes in my head. Meanwhile, it was a fun, if not tiring trip, and I met some interesting new friends to boot!